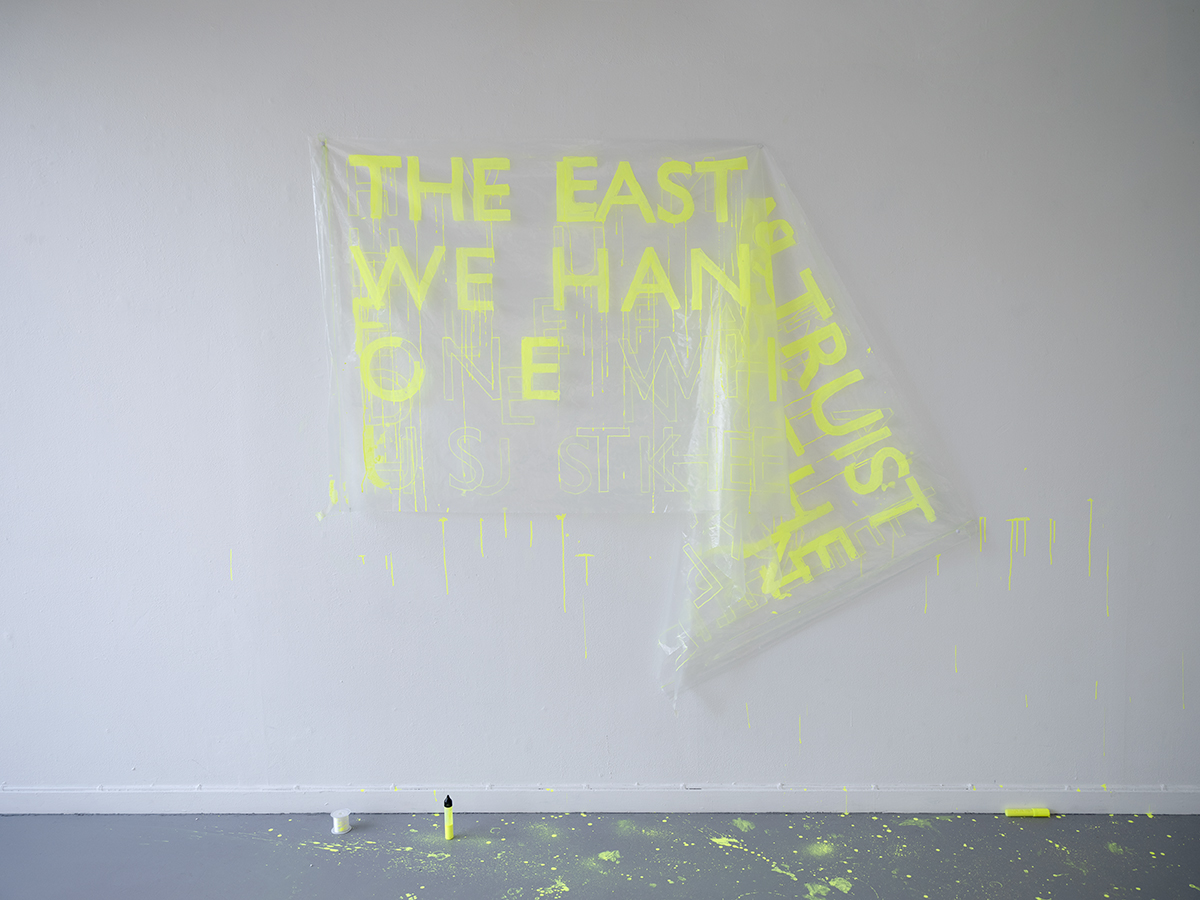

Einar Grinde

«Noe må vi kunne enes om»

Opening: Friday 26 January, 18:00–20:00.

26 January – 3 March 2024

Opening hours:

Thurs–Fri, 16–19

Sat–Sun, 12–16

The title of the exhibition “Noe må vi kunne enes om” (“Something we must be able to agree on”) can be read as a question. A statement. A plea for us to get our act together. Or a furious cry of frustration from an artist who sees that things are going straight to hell.

Einar Grinde uses the protest banner as a tool to hammer away at some of the most difficult challenges we face as a society. Even those of us who take pride in marching on 1 May every year tend to associate these banners with something old-fashioned. For me, it brings to mind images of aging union representatives in the LO (Norway’s largest labor organization) in Trondheim retrieving rolled-up banners from the utility closet on the third floor of Folkets Hus. Black and white pictures of Einar Gerhardsen and a packed Youngstorget demanding “The whole population at work”. Nostalgia for a time I never experienced. It’s easy to feel, standing behind the slogans, be it for labor struggle, women’s rights or Palestine, that it’s “We who did not build the country, we who will not inherit the earth” who are walking there. Standard-bearers for political struggles that belong to the past century.

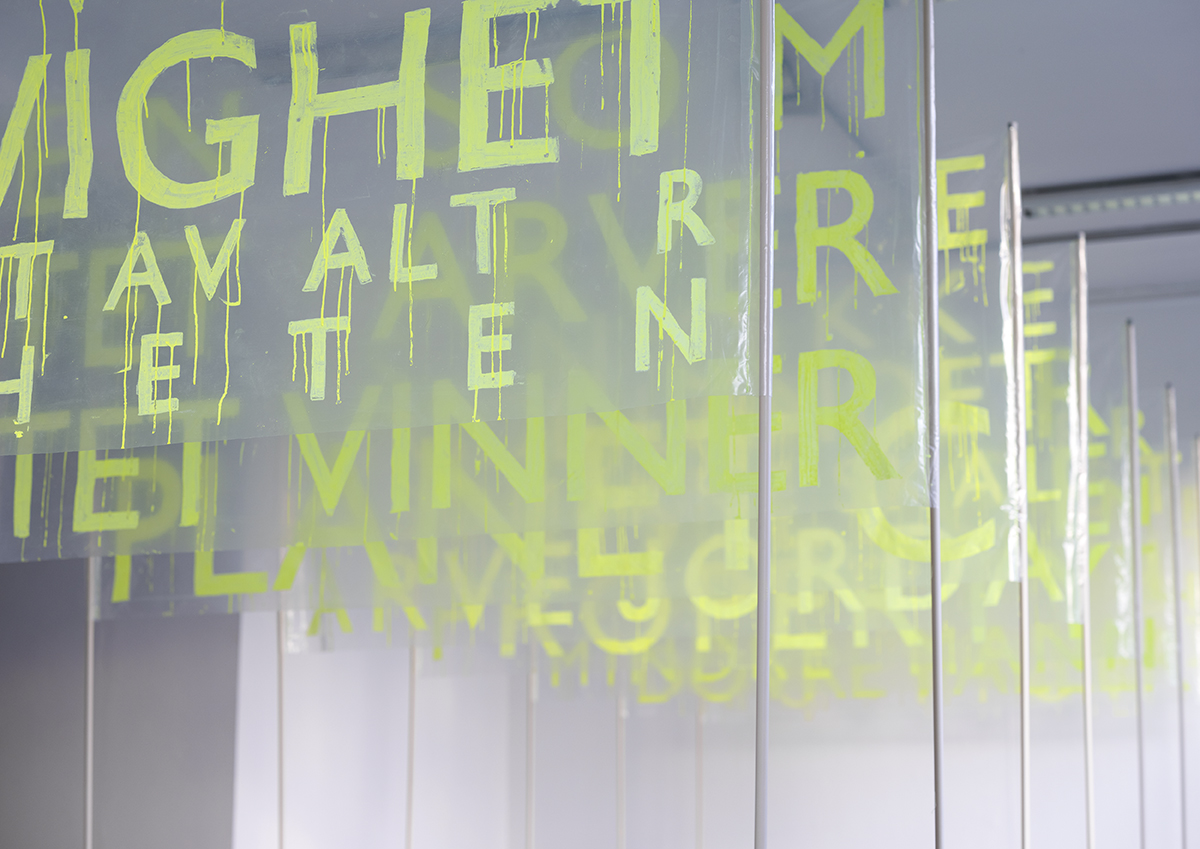

In my encounter with Grinde’s exhibition, I realize that this is wrong. The political banner has more power and is more dangerous than ever, but in a new guise. In the age of social media, the right slogan can hit like a fist straight into a smartphone and turn the world upside down.

The #Metoo-movement sparked an outcry against sexual assault, gender discrimination and oppression in country after country and shook several industries to their foundations. “Black Lives Matter” went from a protest against a police killing in the USA to a protest against racism throughout the Western world. At first glance, “Something we must be able to agree on” could therefore be an optimistic tribute to the regained power of the political slogan. But, on closer inspection, I struggle to find the optimism. Because it can quickly end in FALSE HOPE AND EMPTY THREATS of change. After the police killings in the US, many young people took to the streets. Many times more took to Instagram. Where they posted black photos in their feeds. It only takes one click to be on the right side of history. Protesting is being replaced by performative activism from the couch.

Online activism should not be written off. Social media is an important arena in the battle for minds and attitudes. Yet it is frightening how comfortable those in power are when protest marches are replaced by clicks. Meta, the company behind Facebook, is pumping out progressive banners encouraging users to add to their profile to show that they support the fight for gay and transgender rights and against racism. A company with a record of mass murder and gross exploitation can thus appear progressive. Would they have done so if slacktivism was a real threat? Perhaps they have realized that what doesn’t demand anything of us ends up meaning nothing to us.

“There is no planet C” says one of the works. A dark twist on the climate movement’s “There is no planet B”. Because even this we can’t agree on. In the latest poll, a quarter of Norway’s population doubted that climate change is man-made. And why not? After all, the Norwegian oil lobby has launched its own slogan for a world on fire: “The world’s cleanest oil”. An intoxicated Elon Musk promises colonies on Mars. Planet B existed after all.

Our inability to agree on the most fundamental issue – defending the common means of livelihood – brings to mind the flip side of the slogan. Polarization. Struggle creates change, but also counterforces. Metoo was a showdown with powerful men, but the authoritarian features of parts of the campaign, with the collapse of press ethics and SoMe bullies on a witch hunt, proved to many men that women’s struggle is a struggle against men. “Behind every great man is a lesser man,” and he feels threatened because he can’t wreak havoc at the workplace’s Christmas party like he used to.

When blacks and anti-racists shout “black lives matter”, many hear “black lives matter MORE.” Culture wars against struggles for rights and minorities have become the gasoline that fuels the growth of the far right. In war, it’s not just hard to find something to agree on. It’s treason.

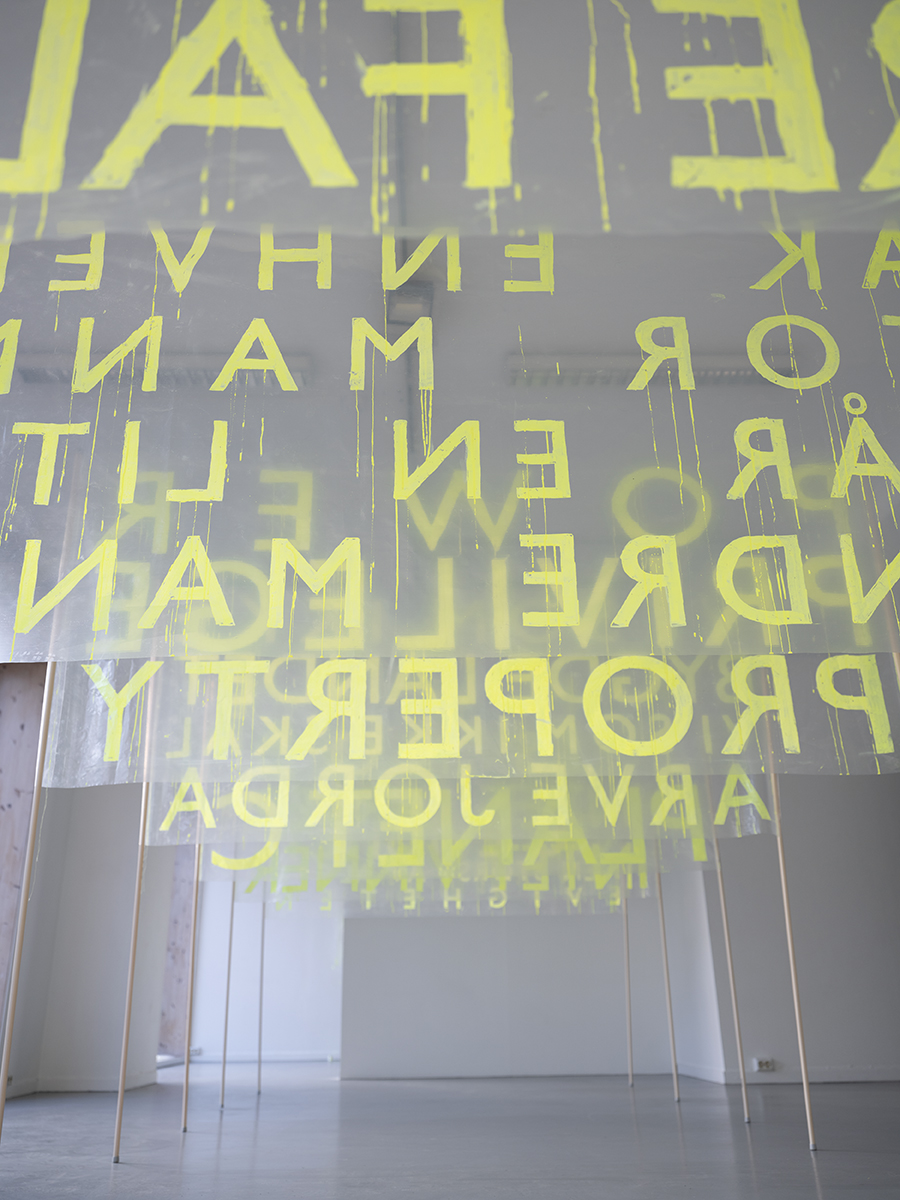

But is there anything we DO agree on? The works “POWER, PRIVILEGE, PROPERTY” and “EVIG VEKST OG TRO TIL DOVRE FALLER” will never be carried in a protest march, but Grinde has given them each their own banner. It’s about time. Perhaps this is the closest we can get to something we as a society have silently agreed upon. It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than another economic system. We are willing to do anything, as long as we don’t have to change anything.

Does that mean that everything is hopeless? I don’t interpret the exhibition in that way. On the contrary, I see it as a desire to find the silent agreement that is hurting us and to find a viable way forward. For me, the title of the exhibition is not a question, a prayer or a frustrated cry. It is a challenge.

– Jo Røed Skårderud

Influencer and journalist for the newspaper Klassekampen

– – –

Photos: Susann Jamtøy / BABEL visningsrom for kunst